The Pull of the Screen or the Promise of the Season?

/There’s a certain kind of glory to spring that makes your breath catch, even on an ordinary Thursday. The tulips are blooming, the robins are nesting, and the air smells like hope. Outside, the world feels young and full of beginnings—graduations, First Communions, Confirmations. Milestones are everywhere, nudging us toward celebration.

But for mothers, this season isn't just for caps and gowns. It’s a commencement of our own. Not the loud, triumphant kind, but the quiet recognition that something is ending—and something else is being invited in. For years, we were in the thick of it—diapers, carpool lines, reheated coffee. Now, we’re still needed, yes—but differently. Or maybe you’re needed across a wide range of ages, stretching yourself so thin you feel as if people can see through you—but not really see you.

The summer is coming; the season will shift. What now?

“Spring isn’t just for commencements in caps and gowns. It’s a season of new beginnings for mothers, too.”

Too often, we try to answer that question by scrolling.

We scroll because we’re tired. We scroll because we’re curious. We scroll because we’re wired to reach for words—those of us who once read cereal boxes just to be reading something. We who once binge-read novels under oak trees and called it bliss now find ourselves reading captions on strangers’ lives while dinner simmers and someone’s soccer kit tumbles in the dryer.

“We who once read cereal boxes and novels under oak trees are still readers at heart—let’s give our minds something worthy.”

But let’s name it: this isn’t reading. It’s reaching. And it rarely satisfies.

Reading has always been our portal—to beauty, to empathy, to the widening of the soul. But we’ve drifted and we’ve replaced sustained focus with scrolling.

It’s still there, waiting. You can read again. Let this be your season to read deeply again.

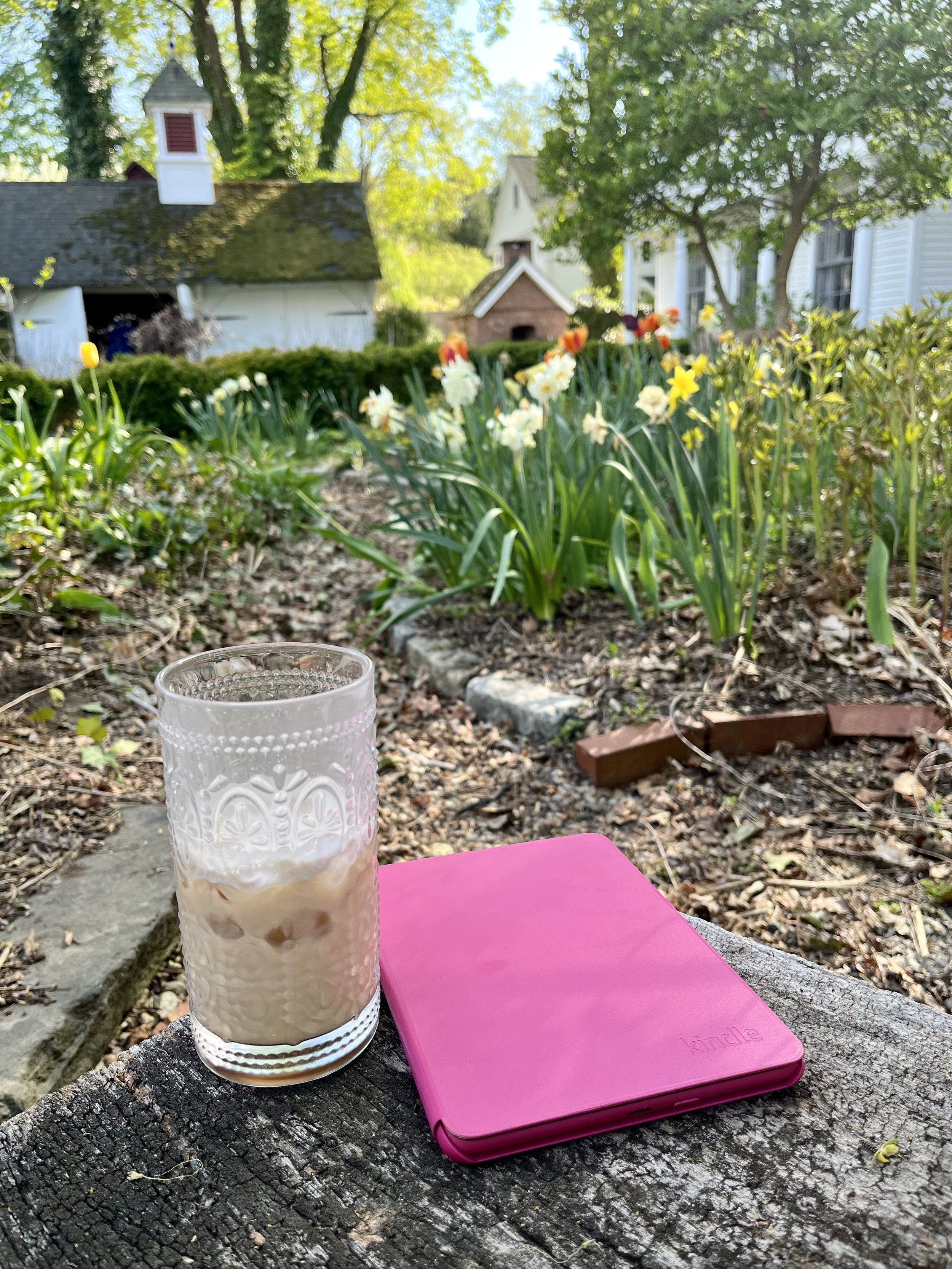

Make it easy. You’re used to reaching for your phone. Train yourself to reach for your Kindle instead. The best decision I’ve made in a long time was the decision to buy a Kindle and a purse big enough to tuck the Kindle inside. Now it goes everywhere with me. Literally. I became a believer on an international trip where I promised myself to avoid screens on my phone. Standing in line for Customs or waiting to board a plane? Everyone around me was scrolling. I was deep in a Katherine Center novel. Later, back home, sitting in a waiting room? I escaped into Rosamunde Pilcher. This one habit switch has changed so much! No more mindless, shallow interactions. Far more opportunities for deep thought and imagination.

A Kindle in your purse can become your secret weapon against the pull of the screen. A novel instead of a feed. A paragraph instead of a reel. A book can take you places. And the Kindle is so much better for you than your phone in so many ways.

The light on a Kindle is kinder than the light on your phone—literally and figuratively. Kindle screens use E-Ink technology, which mimics the look of real paper and offers a reading experience that’s gentle on the eyes. Instead of the harsh glare of backlit devices, a Kindle uses front lighting, which means the light shines onto the page rather than directly into your eyes. It’s a subtle shift that makes a big difference, especially during long reading sessions or quiet nights in bed.

Phones emit blue light that disrupts your body’s natural sleep rhythms. A Kindle, on the other hand, offers a much softer glow with minimal blue light, making it easier to wind down at the end of the day. It invites you to rest. And unlike your phone, your Kindle won’t interrupt your reading with pings or notifications. There’s nothing to scroll, nothing to swipe—just the quiet companionship of words on a page.

Reading outdoors? A Kindle shines here, too—its glare-free screen is easy to see even in direct sunlight. And the battery? It lasts for weeks, not hours, so you never have to stop mid-chapter to hunt for a charger. All of these little differences add up to something meaningful: a space where reading becomes restful again. The Kindle doesn’t just light a screen—it lights the way back to deep, focused attention and the joy of getting lost in a good book.

“A Kindle in your purse can become your secret weapon against the pull of the screen.”

Choosing to read books instead of scrolling social media can be a powerful act of self-care, attention management, and soul formation. This spring, as we head into a summer full of choices, consider this an invitation (or a challenge if that’s more inspiring) to reclaim your attention and your imagination. Here are some reasons to ponder and to remind yourself of when you’re tempted to scroll.

1. Deep Focus vs. Fragmented Attention

Books encourage immersion. They invite your mind to slow down, settle in, and think deeply.

Social media, by design, keeps your attention jumping—training your brain to crave quick hits instead of depth.

2. Mental Health Boost

Reading reduces stress and anxiety. It offers restful escape and quiet moments to breathe.

In contrast, endless scrolling can heighten anxiety, feed comparison, and leave you feeling drained.

3. Rich Vocabulary & Imagination

Books—especially good ones—fill your mind with new words, ideas, and images.

They build imagination. Social media often shrinks language to headlines, emojis, and sound bites.

4. Nourishment for the Interior Life

Books shape your interior world. They feed empathy, patience, and understanding.

Scrolling tends to inflame reactivity, replacing contemplation with quick judgment.

5. Better Sleep & True Rest

Reading before bed calms the mind and helps your body transition to rest.

Screens and social feeds often do the opposite—stimulating the brain and disturbing sleep patterns.

6. Agency & Identity

Choosing a book is an intentional act of formation.

Scrolling is usually reactive—what you see is chosen by algorithms, not by you.

7. Formation, Not Just Information

Books don’t just inform—they transform.

They stay with you, echoing in your thoughts long after the last page.

Social media, on the other hand, often overwhelms with quantity rather than meaning.

“Don’t just scroll through someone else’s life—create your own vision and step into it.”

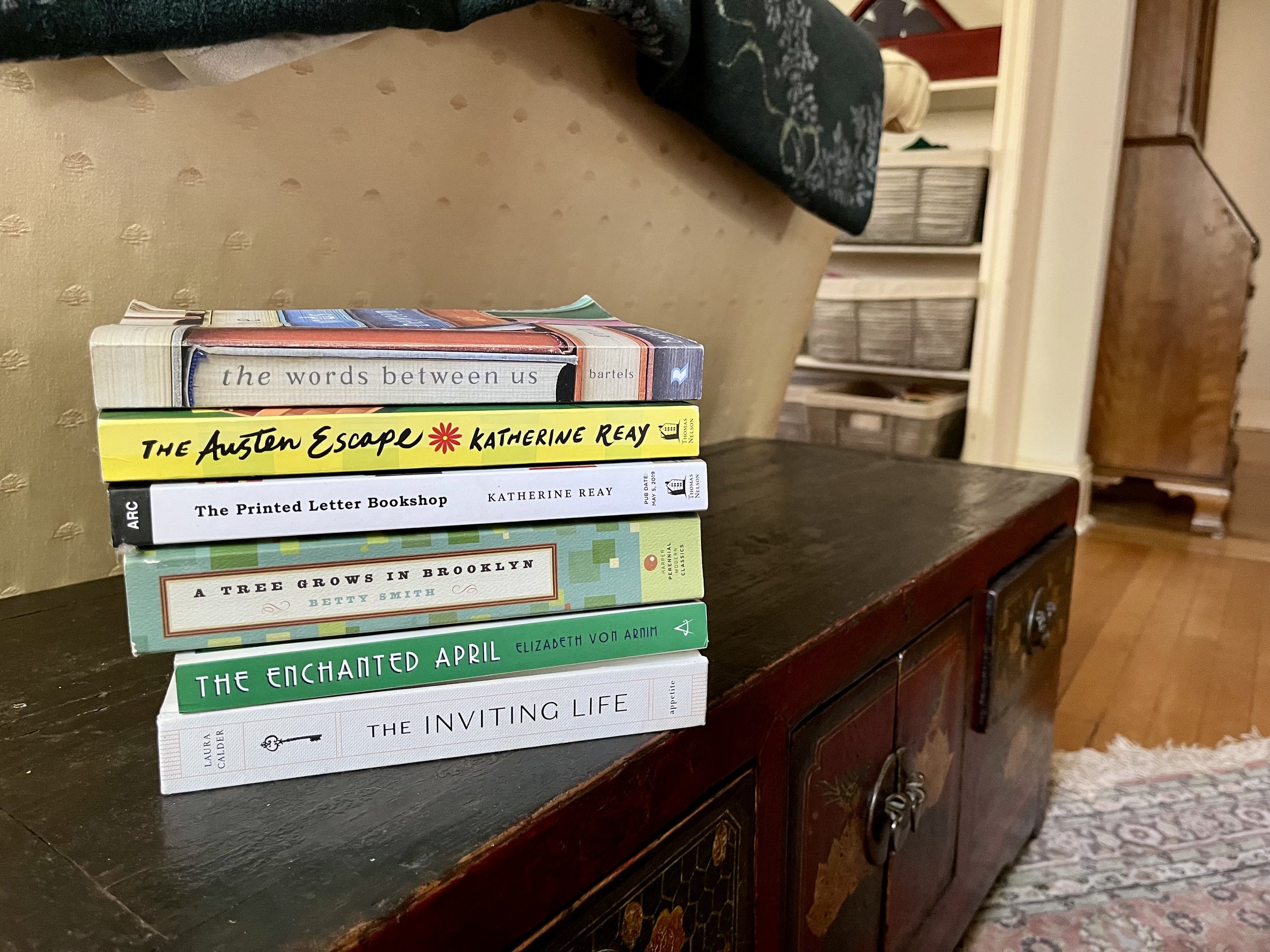

What to Read This Spring (Instead of Scrolling)

Literary Fiction That Feeds the Soul

Gentle Reads for Waiting Rooms or Tired Days or Long Summer Walks

Miss Buncle’s Book by D.E. Stevenson

The Shell Seekers by Rosamunde Pilcher

The Blue Castle by L.M. Montgomery

The Berlin Letters by Katherine Reay ($2.99 on Kindle right now)

Biographies of Women Who Lived Beautiful Lives

Be Ready When the Luck Happens by Ina Garten

Becoming Mrs. Lewis by Patti Callahan

A Circle of Quiet by Madeleine L’Engle (free with Kindle Unlimited)

Non-Fiction for Curiosity and Contemplation

Still: Notes on a Mid-Faith Crisis by Lauren Winner ($2.99 on Kindle)

The Art of the Commonplace by Wendell Berry

Everything Sad is Untrue by Daniel Nayeri

We all have books that mark a turning point or a milestone in our lives, books that have shaped us or been pivotal in some important way. What are yours? Can you share them in the comments and help us find them, too?

Psst: Want to Go Deeper?

If this resonates, come join the conversation in our Take Up & Read membership community. We’re reimagining what it means to grow in wisdom, creativity, and connection. and we talk about books quite a lot. There’s more for you here—quiet joy, deep thought, and good company. so much better than scrolling.